Defective Blocks

The Issue

Emerging Science

The scandal came to light in 2011 when defective blocks used in the construction of multiple dwellings exhibited signs of decay. According to the Report of the Expert Panel on Concrete Blocks, published in June 2017, the issue was made public in 2013. The Expert Panel was established by Mr. Paudie Coffey, T.D. in April 2016 and concluded that the concrete blocks were not fit for purpose due, in the case of Donegal, to excessive Mica content of the concrete blocks and in the case of Mayo, the excessive content of pyrite. It should be noted that the report relied on tests carried out by homeowners and no tests were carried out by the expert panel. It is unclear at present whether this issue extends to the concrete produced for the foundations and ground floors of the affected buildings, however, given recent emerging scientific research, this is likely.

Emerging science contained in the peer reviewed article titled, The “mica crisis” in Donegal, Ireland – a case of internal sulfate attack[1] presents a compelling argument, backed by in depth analysis, that the issue of the defective concrete blocks is not due to mica content, instead, the deterioration process is caused by the oxidation of pyrrhotite and the subsequence chemical reactions that can be divided into three phases:

1. Expansion phase leading to concrete cracking (the expansion is caused by the formation of a sulfate mineral called “ettringite”)

2. Strength loss phase (the strength loss is caused by the formation of a second, very soft sulfate mineral called “thaumasite”).

3. Carbonation phase (due to uptake of carbon dioxide) from the air the sulfate minerals disappear as they are transferred to gypsum.

The findings of the report are based on samples from the concrete blocks of four houses. The authors call for further research to be undertaken, including, most crucially, investigations into whether the structural foundations of the houses have been similarly compromised by the presence of pyrrhotite. It seems highly unlikely that the manufacturer used different aggregates for use in ready mixed concrete and the defective blocks, so it is highly likely that the foundations of the houses are also defective. Anecdotal evidence is emerging that confirms this.

The extent

The extent of the issue is currently not quantified. Surveys of the number of self-reported properties effected have been carried out by the Mica Action Group but to these surveys have not been made public. It is also not clear when the manufacture of the defective blocks commenced. The expert panel report presents anecdotal evidence that structural issues have manifested in houses built as far back as 1984 but the majority of the reported issues occur in houses that were built between 1999 and 2006. This timeline includes the ‘Celtic Tiger’ which saw a massive surge in the number of buildings that were constructed in Donegal. The Wikipedia article on the ”Mica Scandal”[2] states that more than five thousand houses are affected.

Response

To formulate a considered response to the problem, the problem needs to be clearly quantified with the severity of the issues facing homeowners categorised in groups of urgency of the response required. Following this, an appropriate strategy, prioritised to help those in most urgent need, can be determined.

Size of the problem

The scale of the issue is daunting; however, it also presents an opportunity to rebuild the housing stock taking into account the current climate crisis. The adoption of a ‘fabric first’ approach to the reconstruction and the inclusion of various new renewable technologies to service the houses and create a stock of carbon zero homes (in-use) where the running costs are reduced to maintenance regimes.

Identifying the issue

When did it start?

The problem of defective concrete blocks is detrimental to thousands of households in Donegal. Exactly when the issue began and the geographical extent of it is currently unclear. The report that housing built in 1984 exhibits structural defects is alarming.

Ramifications for all residents

Even if a building built in northern Donegal since approximately 1997 does not physically have a “mica” problem, the owners of the property still have a “mica” problem as they cannot realistically sell their house without a certificate confirming that it is not affected by the issue. Local residents also attest that obtaining property insurance on these houses is proving to be increasingly difficult.

Compiling the data

What we would like visitors to this website to help with is filling in the missing data:

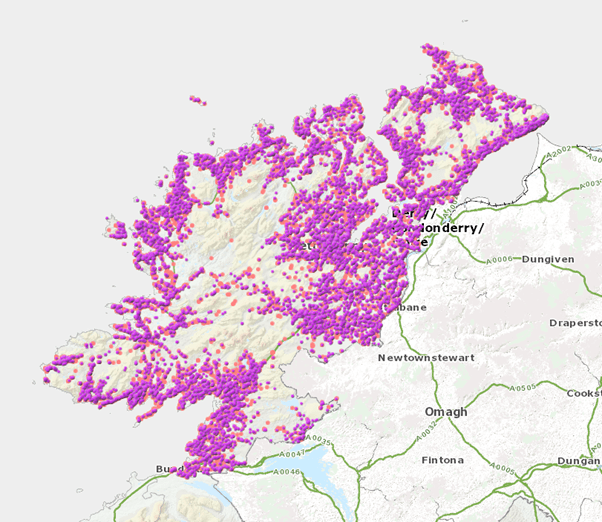

The potential geographical area affected. The below image is taken from the Planning Application Locator for Donegal County Council and shows the planning applications between the years 2000 and 2009:

© Ordnance Survey Ireland

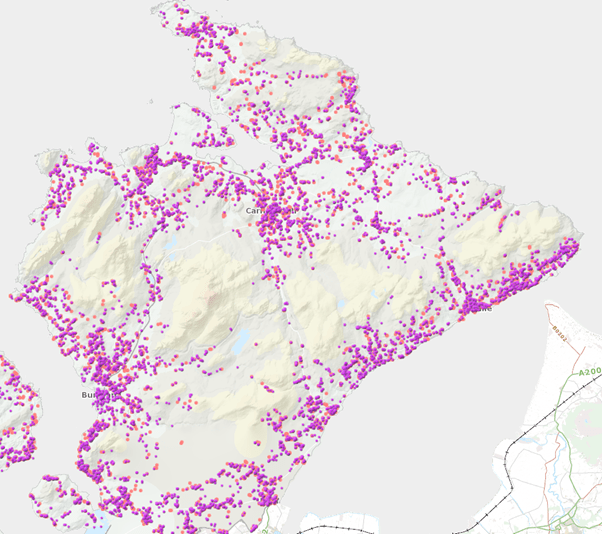

Below shows the Inishowen planning applications between the years 2000 and 2009

© Ordnance Survey Ireland

Formulating a response

Government strategy

The government strategy is that reconstructed defective blocks homes are rebuilt to the Building Regulations applicable the year they were constructed. This strategy means that the walls, floors and roofs of the reconstructed homes do not need to be as insulating as a house built to the current regulations. Given the current climate emergency, we think this is the wrong response. The government has the opportunity to reconstruct the defective block homes as net-zero homes, something that Teach Modúlach will campaign for if given the mandate to do so.

Alternative construction method

Arguably, the crisis has been so detrimental to the public perception of blockwork construction that rebuilding in blockwork would most likely be rejected by those directly affected. Additionally, the use of concrete to rebuild the housing stock would release a huge amount of carbon, a dubious strategy in the era of the climate catastrophe we are currently living in.

[1] The “mica crisis” in Donegal, Ireland – a case of internal sulfate attack?

Authors:

Dr Andreas Leeman – Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland & School of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Ulster University, Coleraine, Northern Ireland

Barbara Lothenbach – Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland & NTNU, Department of Structural Engineering, Trondheim, Norway

Beat Münch – Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland

Thomas Campbell – TA Group, Kiltimagh, F12 Y6VO, Ireland

Paul Dunlop – School of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Ulster University, Coleraine, Northern Ireland

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mica_scandal